When has a man been so well regarded in our nation’s history that we made him President without a popular vote by the people?

When has a man been so well regarded in our nation’s history that we made him President without a popular vote by the people?

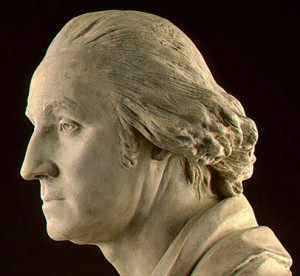

George Washington was that man.

He was chosen by 69 electors to be our first President.

The attributes that commended him for such an historic appointment should be the measure of our elected representatives today.

Parson Mason Weems told a story, demonstrating Washington’s honesty – that George had confessed the truth to his father that he had chopped down a cherry tree. This act of contrition was a fable. Not true at all. In truth, in 1743, when George was 11, his father, Augustine, died. George did, however, concern himself with building character. Before his 16th birthday, George compiled 110 “rules of civility and decent behavior in company and conversation.”

The first rule was that “every action done in Company, ought to be with some sign of respect, to those that are present.” His variation on the “turned cheek” of scripture was, “Shew not yourself glad at the misfortune of another though he were your enemy.” Another that our modern political dialogue could learn from was: “Let your conversation be without malice or envy, for ‘tis a sign of a tractable and commendable nature: and in all causes of passion admit reason to govern.”

Washington was thus fortified for his life’s journey.

When he was a 21-year old Commander and clashed with the French where Pittsburgh now stands, the French overwhelmed his force, knocked him off his horse twice, put four bullet holes in his coat, and sent him home disarmed.

George said, “I have heard the bullets whistle and, believe me, there is something charming in the sound.”

Upon his return to Virginia, he was made a colonel, at 23, and named commander-in-chief of the Virginia forces to defend the frontier. Long before Valley Forge, he learned the challenge of severe shortages and how to survive.

So many have idolized Washington, they’ve denied his humanity, quite impressive in and of itself.

George was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1758, on his third attempt.

After Lexington and Concord, Washington appeared at the 2nd Continental Congress in full military dress; the Congress chose him as the Major General and Commander-in-chief of the Continental Army.

Washington was able to force the British to withdraw from Boston, but he had to lead his army in retreat in New York, first across the East River and then, after a valiant defensive fight up the island of Manhattan, across the Hudson River to New Jersey.

Morale was low, enlistments were about to expire, desertions mounted, supplies were insufficient, and his own generals had a low opinion of the man that we too easily mythologize today.

Yet, against these obstacles, Washington made dramatic and heroic crossings across the icy Delaware River waters and defeated the Hessian force in Trenton, New Jersey, on December 26, 1776.

Thomas Paine released a pamphlet decrying “the summer soldier and the sunshine patriot,” reminding his readers that “tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered.”

On February 16, 1778, Washington wrote from Valley Forge of “the present dreadful situation of the army for want of provisions” including “a famine in the camp” and soldiers “naked and starving.”

Washington survived and so did a portion of his army and, with the help of Admiral de Grasse’s French Fleet, trapped General Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia on September 28, 1781.

When Washington finished his second term in 1796, he warned in his farewell address against breaching the union of the states born under the Constitution that he helped formulate. He said, “there will always be reason to distrust the patriotism of those who in any quarter may endeavor to weaken its bands.” Anticipating the contract doctrine by which a state might wrongly claim it could withdraw from the union, he warned, “a government for the whole is indispensable” and that “no alliance, however strict, between the parts can be an adequate substitute.” Washington dismissed “all obstructions to the execution of the laws … under whatever plausible character, with the real design to direct, control, counteract, or awe the regular deliberation and action of the constituted authorities” as destructive and “of fatal tendency” for “they serve to organize faction” and “give it an artificial and extraordinary force.”

Washington’s distaste for factional parties had to do with “the alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge” and how that could lead to a “frightful despotism.”

Washington warned that factional parties “agitat[e] the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindl[ing] the animosity of one part against another.”

Washington exhorted that it is “the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.”

When he was a young man, Washington’s last rule of civility was: “Labour to keep alive in your Breast that Little Spark of Celestial Fire Called Conscience.”

Plainly, Washington had more than a spark when he bid the nation farewell.