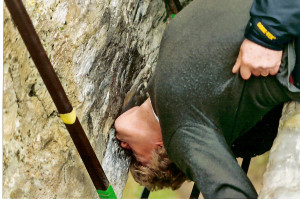

Some have jokingly said it was unnecessarily redundant, even dangerous, that I felt it necessary to kiss the Blarney stone, a block of bluestone found at the heights, in the parapet of the Blarney Castle, enchanted by the goddess Cliodhna, for its fabled gift of gab and flattery.

You tip the kind strong rain-garbed guard who holds you from falling as you lean backward.

We were told one soldier did fall, long before, perhaps after a pint, slipping between the walls, sliding to the ground, landing on his head, speeding him on his way to his final heavenly reward.

It was a somewhat rainy day when I underwent this transformation, bending backward, without fear of contracting anything even remotely dangerous to my health – as we are all related who kiss this grand stone, just like every member of a Catholic congregation may drink safely from the same Holy Communion cup

It’s more apt for a lawyer, however, to kiss this Irish stone as, according to the legend, it was this stone that Cliodhna first commended to the builder of the Castle so that he could plead his case in court successfully.

I traveled to Ireland because I felt an affection and empathy for a people I hardly knew.

The Flannerys come from the West Coast of Ireland from County Mayo where the saintly Patrick launched his mission to save the souls of Ireland.

The Flannerys traveled to America’s Dublin, the “Big Apple,” in the late 19th or early 20th century. It was as likely an adventure to find the mythical gold lined streets of New York as it was to escape the English oppression that was cruel both in its economic and political dimensions

The growing sea-going Irish diaspora that found its way to America found no gold in the streets. More often, they found out of work and hungry Irish in the streets. They also found “their kind” slighted, slandered and suffering, quite comparable to the suffering they’d had in their Irish homeland.

I heard at a coffee shop off the Berlin Turnpike recently a woman loudly proclaiming, oh so certain, how “in the past” families “quickly assimilated,” especially the Germans, she said.

I did not hear her say what people she thought were so tardy in their “assimilation.”

In Lovettsville, where I live, we celebrate how it was a German and Irish settlement before the American Revolution.

By the time I was born in the South Bronx, I was of course quite removed from the “troubles” in Ireland and America that so sorely bedeviled my Celtic lineage.

There was evidence, however, that Irish were still not quite acceptable, even on my watch. Among the “Ks” the KKK hated so much were the Catholics. There was plenty of literature how four-time New York Governor Al Smith from the lower east side lost his bid to be President in part because he was Catholic (and perhaps sounded too New York nasal). In 1960, Jack Kennedy had to reassure America that the Roman papacy would not dictate his public duty. Even when I was a kid, there were jobs and clubs and plenty more for which the Irish Catholic need not apply.

Like other immigrant groups, the sustaining resolve, to resist the swirling hateful waters of discrimination, and enforced isolation, comes from a dream.

Yeats wrote, “The Irish dream things that the world has never seen.”

Those who dream, are spurred to fight, to make their dreams – that others have never seen before – a reality, and, because they believe they can get it done, don’t know any better, they succeed.

The Irish in America, enriched by the strong blood of immigrants from other nation-states, made the grand difference they have in war and peace, in law and politics, in art and music, both in their adopted homeland and throughout the world, because they had a dream.

A fitting resolution for this St. Patrick’s Day would be to think long and hard about how we mis-treat the immigrants we warmly invite to join our democratic experiment by the words found inscribed on our Statute of Liberty and decide to do better than we have, for our people are what’s good about America and the key to what greatness we may yet achieve.