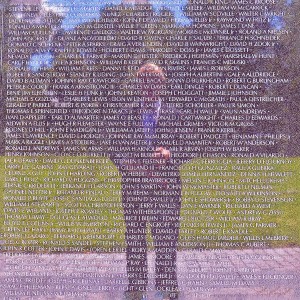

We have had another Memorial Day and remembered the sacrifice of the men and women who served this nation.

But we really should be doing a lot more than simply – “remembering them.”

We must do better and demand that our elected and appointed officials “do something.”

My late uncle, Charles Flannery, served in the armed forces led by General Patton when the Allies attacked by way of Sicily, landing on the beaches of Italy.

Charles was shot in the chest, lifted off his feet, spun around, knocked unconscious, and taken prisoner. He returned home quite emaciated.

Years after the war, Charles died in a hospital in the Bronx that, according to my elders, refused to give him more blood, to save him from that earlier chest wound.

Ours was one family, as young as I was, that resented the nation’s unfulfilled promise to our Uncle Charles.

Our nation has been long on promises to vets when leaving our shores to serve our nation abroad, and quite uneven, often indifferent, falling way short to meet their needs, upon their return home broken and damaged by their service at war.

One clear indication of how we are currently failing our service men and women is the statistic that we lose so many soldiers upon their return to suicide.

It has a lot to do with the fact that as high as 30 percent of our Vets from Iraq and Afghanistan, according to some studies, suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder but don’t receive the care that might erase or mitigate this wake-a-day night mare.

Others suffer traumatic brain injuries – most often concussions from one or more bomb blasts – that went untreated.

There has also been corruption. The VA has falsified the wait times, the back log, for vets to receive appointments and treatment. This was uncovered in 2014 and four VA Chiefs later, it’s still going on, but not as much, and little has improved the efficiency of the agency’s 1,240 hospitals and clinics. Partly, the answer is that the VA has great trouble recruiting physicians to care for the vets.

45% of those returning from Iraq and Afghanistan have suffered compensable disability injuries.

Whatever the cost, and it is significant, we handle these claims very slowly.

The “system” is overburdened and can’t handle the load. We are told. So why don’t we add the staff necessary? Or, is this how we suppress the cost of paying these claims?

There are thousands and thousands of disability appeals (notices of disagreement with a VA decision), one out of five appeals, distributed throughout the eight regional offices across the nation, almost entirely ignored in the past by VA regional offices. But there has been a legislative fix that has contributed, at the least, to the transparency of that process.

When our service men and women return from the theaters of war, hundreds of thousands of vets are doing time in prison or jail because of substance abuse or mental health. Half of our vets in custody are there because of drug offences.

We shouldn’t have a society that criminalizes a person who requires treatment, needs healing and is not involved in any drug dealing. Chronic pain is an issue that many Americans struggle with. In fact, about 30 percent of Americans suffer from some form of long-term pain. Veterans, on the other hand, deal with frequent and constant pain at an even higher rate — 60 percent of those previously deployed in the Middle East and 50 percent of older veterans experience chronic pain. We have to do better and recognize that these vets will commit suicide if they can’t get relief from the pain they suffer.

We are failing to honor those who have been injured mentally as well as physically.

We should be ashamed when we remember Veterans who sacrificed their lives on Memorial Day, and praise them on Veterans’ Day, and the rest of the year, we fail to do what’s necessary to heal, treat, and repair them.