In 1957, a brilliant silver ornament streaked across the sky and my still young eyes could see what we learned was Sputnik, a Russian satellite.

The space race was on and many of us wanted to go to space, to know about physics, to fly if we could.

This was the new frontier, our own Wild West now tamed, that exploration concluded, we were setting out on the imaginary path implanted in our young minds by those old style black and white Buster Crabbe “Buck Rogers” flicks. But this was the real deal, we were really going to do it.

A young president with a strong nasal cadence said we were going to the Moon – and he meant it.

In High School, I took a calculus class at the university, and my professor invited some of us to learn how to program computers. That seemed like an entry-level job into the space program, NASA here we come, not really, but it felt like it.

In 1969, I bought a BSA motorcycle in London and took off across the English Channel from Dover to Calais to tour “the continent.”

In July 1969, I found myself in a small village south of Paris on the windy road to Marseilles and the Cote D’Azur.

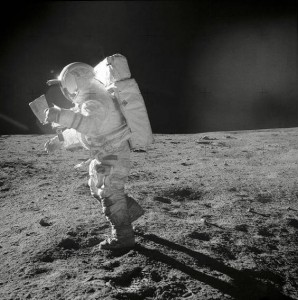

The towns people asked in French if I was American – “Je suis un Americain” – I said – exhausting most of my French – they laughed and they brought me into a local cafe and, on the TV, they pointed, there was a man walking on the Moon, Commander Neil Armstrong.

We were like a family, they toasted all that was American, and I gave some of the town’s youngsters a ride on my bike, up and down the main street. We were all heroes. I was the American representative of an America that was the greatest. We had done what Buck Rogers imagined for us to do, we traveled in space, put a man on the Moon and brought him home.

In years since, it has become a tired refrain when the question is, “could we do one thing or another?,” and we say, “We put a man on the moon” – like we could do it now.

True, we did it, but it was a mission, we were all part of it, an ensemble production, it defined our resolve to accept a challenge no one had ever done before. We were all in it together.

I had a case in Florida years ago and an award-winning journalist, Melissa Holsman, thought I’d enjoy meeting a friend of hers who walked on the Moon, Edgar Mitchell.

We had a long pasta dinner together, talking all the time about what it was like, what he thought now, and he took me to his home and showed the dust he retrieved from the surface of the moon, a camera he kept, and some other mementoes.

These were items the astronauts were told they could keep as long as the weight didn’t change the allowable payload.

Edgar was a hero – the real deal.

Edgar said, after his moonwalk, “You develop an instant global consciousness, a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it. From out there on the moon, international politics look so petty.”

Probably because I knew Edgar, I got to represent all the astronauts who were assigned a Moon mission.

NASA was upset that some astronauts were selling off their moon mementoes, 40 years after they’d been to the Moon, and NASA wanted these tokens surrendered.

We pushed back on that bad idea, reminding NASA of the promise made many years earlier, and congress did as well. NASA relented.

In the bargain, I got to meet the most amazing living adventurers you could imagine. When we talked together, at the hotel where they stayed, they had so many ideas and each different, well stated, and with energy, but then there was a shifting in the discussion, a synthesis, they’d pull together into a team with one mission, one plan.

You could understand what happened on Apollo XIII after Mission Commander Jim Lovell told Mission Control, “Houston, we have a problem.”

There were many stories to tell that reveal their heroics but Commander Gene Cernan, Apollo 17, the last to hop and drive and walk upon the moon almost didn’t make the cut.

He misgauged his flying height above the reflecting Florida waters near shore and crashed a copter on a practice run, surviving himself, by swimming underwater clear of the fiery waters.

It was suggested by NASA that he could say that the crash was “instrument error.”

He insisted it was his human error, knowing that the honest admission would likely scrub him from the last Moon mission.

He acted with integrity, at the risk of losing what he wanted to do so badly. He told the truth. The kicker is he made the mission.

It was the mark of all these men – what made them heroes – the risk of life and character to go where no one and then — only few men have gone.

Gene said this on that last Moon mission – “This is Gene, and I’m on the surface; and, as I take man’s last step from the surface, back home for some time to come – but we believe not too long into the future – I’d like to just [say] what I believe history will record: that America’s challenge of today has forged man’s destiny of tomorrow.”

Where are the heroes today – the promised destiny that Gene imagined?

Where is the national resolve to do something great and lasting?

Today our public promises are closer to Buck Rogers in the sense that they are ideas, images, but no one is doing the hard work to make them real, to do what no man has done before, on this small blue planet or out there in the heavens above.