One of the first books I read was James Fennimore Cooper’s, “The Last of the Mohicans.” Cooper also wrote, a book titled, “Redskins,” a term much discussed, and rightly so, these days.

In March 2013, Cooper’s hometown, settled by his father, retired the High School’s team name, the “Redskins.”

When I watched tv as a boy, or went to the local movie house, it was cowboys killing savage “redskins.”

Cooper wrote in his book, “Mohicans,” that, “History, like love, is so apt to surround her heroes with an atmosphere of imaginary brightness.”

Consider General Jeffrey Amherst, the Commander-in-Chief of the British Forces. In 1763, Amherst sought to exterminate Indians by injecting blankets given to American Indians with small pox.

Most Americans look at the large sculpted heads on Mount Rushmore of Presidents Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt, and they see the founding fathers – they see heroes.

The surviving descendants of indigenous tribes observe a somewhat dimmer image of flawed men who sought to destroy their race.

In 1799, General Washington gave orders to “lay waste to all the [Iroquois] settlements around … that the country may not be merely overrun, but destroyed.”

In 1807, President Jefferson said, “…if ever we are constrained to lift the hatchet against any tribe [,] we will never lay it down till that tribe is exterminated or is driven beyond the Mississippi.”

President Lincoln in December 1862 ordered 38 members of the Dakota Sioux Nation hung for fighting for the food our government promised for their land – but then failed to provide.

President Roosevelt, a self-described Indian fighter, said, “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are dead Indians, but I believe nine out of ten are, and I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth.”

Sherman Alexie, a Native American from a Spokane tribe, and an award-winning writer, wrote a poem titled, “Vilify,” about the presidents immortalized on this mountain monument, and said, “I know every president, no matter how great on the surface, owned a heart chewed by rats.”

In 2011, Dalhousie University Professor Susan Sherwin wrote “the greatest danger of oppression lies where bias is so pervasive as to be invisible.”

The bias is that we consider the original Americans we supplanted as savages, red of skin, the color of rage, of blood, of passion and violent. We so accept this racial slur, without question, that we may be surprised when a tribe elder responds, “Does my skin look red to you?”

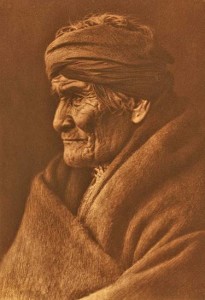

Simon Moya-Smith, a citizen of the Oglala Lakota Nation, found it disappointing and offensive that the Navy Seal Code name for Osama bin Laden was “Geronimo,” a name highly regarded in the American Indian Community, and yet an aptly derogatory slur by our government for the criminal master-mind of 9-11.

Every dictionary describes the word, “redskin,” as a racial slur. The UN says, it’s a “hurtful reminder of the long history of mistreatment of Native American people in the United States.”

Half the United States Senate has written Dan Snyder who owns the Washington football team, asking him to change the name.

Snyder’s Custer-styled remark is – he will “NEVER” change the name.

Snyder receives about $4 million dollars in tax payer funds to subsidize his training camp in Virginia, and $70 million from Maryland to build the stadium where the games are played. The public therefore has some right to demand, “Dan, change that name!”

Amanda Blackhorse, a Navajo, is the lead plaintiff in the Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) action that recently confirmed the obvious, that the name of the Washington team is a disparaging racial slur.

Some have asked Amanda what she’d say to Mr. Snyder given the opportunity.

Amanda said, “I’d ask him, ‘Would you dare call me a redskin, right here, to my face?’”

Come on, Dan, tell us you wouldn’t call her a redskin, and change the name!