In 1908, there was a statue erected of a confederate soldier, rifle drawn, standing vigil before the Loudoun County courthouse, as if an armed sentry demanding that any person approaching the court must first seek permission to proceed any further.

No one asks why this statue was not erected sooner than 40 years after the Civil War.

No one is curious why the citizens didn’t forge a statue of a Union and Confederate soldier standing side by side, at peace, weapons at rest, given that Loudoun County had civil war combatants on both sides of that divisive struggle.

It’s because this statue was never intended to bring us together.

Consider the historical context in Virginia after the Civil War.

In 1868, a Richmond editorial praised the KKK for “not permit[ting] the people of the South to become the victims of negro rule.”

Even the 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution, granting Black men the right to vote, did not prove an effective remedy.

Racial segregation appeared and persisted. A white dominated political system established itself throughout Virginia. From 1880 to 1930, mobs in Virginia executed seventy blacks.

In 1890, a local Hamilton contingent of blacks formed the Loudoun County Emancipation Association “to work for the betterment of the race – educationally, morally and materially.”

In 1896, the Supreme Court shored up segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson pronouncing that “separate” was just fine for Blacks.

In 1902, the hateful Klan was summoned back into service. Thomas Dixon, Jr., a fiction writer, favoring white supremacy, told the nation that the Klan was an heroic force. The Virginia Constitution was amended to limit the voting rights of Blacks, by requiring screened interviews in order to vote and imposing a poll tax. The number of black voters in Virginia declined from 147,000 in 1902 to less than 10,000 by 1904.

Harvard-educated W. E. B. Du Bois urged Blacks to engage in “ceaseless agitation and insistent demand for equality.”

This was the environment that prompted the placement of a statue, of a Confederate soldier, in the court house green in 1908.

In 1909, the next year following, NAACP lawyers began in earnest to end segregation.

There were lynchings again.

At long last, in 1954, in Brown v. Board of Education, the NAACP’s Robert Carter convinced the Supreme Court that separate was most certainly not equal.

In 1963, the Reverend Martin Luther King reminded the nation that despite the century-old emancipation declaration, “the life of the Negro [was] still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination.”

After the recent racist killings in a church in Charleston, SC, the Reverend King could say today, as then, “this is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.”

It is time to replace that statute erected not to honor combatants celebrating a unified peace but to war against equal rights.

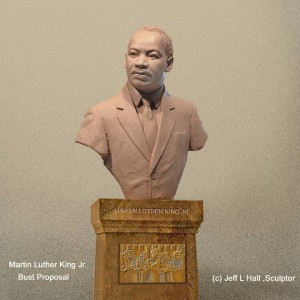

We must replace that statue with an heroic bust of Martin Luther King (pictured above), already modeled, created by a world renowned sculptor, Jeff Hall, of Lovettsville, Virginia.

We propose this be done at County expense, for about $30,000, a small fraction of what we spent on the County’s controversial marketing agreement with the Redskins.

We should pay for this, not as reparations, but as a testament by the entire community that we support equal rights and equal protection before the law, and though, we were once divided by civil war, and by an ongoing struggle for equal rights, we now stand united and wish – as the Reverend King once urged – to “let freedom ring.”