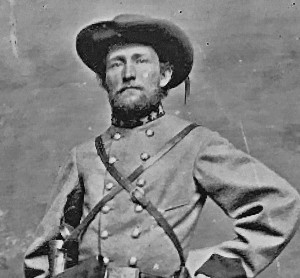

Most of us are familiar with “the Gray Ghost,” John Singleton Mosby, a Confederate Army Cavalry Battalion commander in the Civil War, a guerilla fighter leading irregulars in Northwest Virginia, and throughout Loudoun County, known for raids on the Union forces and getting away afterwards, thus the appellation, “ghost.”

I’ve always found Mosby fascinating, but more for what he did after the Civil War, transformed, serving as a lawyer and public servant, and mending a nation divided. We might learn from his character by mimicking today how Mosby acted then.

When the Civil War began, Mosby spoke out against secession, but joined the Confederate army as a private; it was his civic duty, he said, to fight for his “country.” Mosby found a way to reconcile these difficult choices.

Herman Melville wrote a poem, warning – “Of Mosby best beware” for “mounted and armed he sits as a king” and “each alley [is] unto Mosby known” as his battalion “kill[s] and vanish[es] … through grass they glide” and “[t]o Mosby-land the dirges cling.”

Union General Ulysses S. Grant described Mosby as “slender, not tall, wiry and [he] looks as if he could endure any amount of physical exercise. He is able, and thoroughly honest and truthful.”

Mosby said after the war that “whoever has seen the horrors of a battlefield feels that it is far sweeter to live …” Mosby was not the first soldier to understand that working for peace and comity is much to be preferred but to make this adjustment so quickly after a civil war is quite remarkable.

Mosby knew that “we went to war on account of the thing we quarreled with the North about.” He said, “I’ve never heard any other cause than slavery.”

After the war, he practiced law and lived in Warrenton, Virginia. Many have appeared in the same courthouse where Mosby argued causes. Mosby was, however, harassed after the war, some tried to kill him, but what was surprising was that General Grant granted Mosby an exemption from arrest and guaranteed his safe conduct and Mosby wrote that otherwise he “should have been outlawed and driven into exile.”

Mosby thanked President Grant for the courtesy and played a part in obtaining amnesty legislation for former Confederates.

“Like most Southern men,” Mosby said, “I had disapproved the reconstruction measures and was sore and very restive under military government; but since my prejudices have faded, I can now see that many things which we regarded as being prompted by hostile and vindictive motives were actually necessary in order to prevent anarchy and to insure the freedom of the newly emancipated slave.”

Mosby had the discipline of mind and respect for the law to work toward a national re-union that others couldn’t even begin to understand. Thus did Mosby undergo his own emancipation in the freedom from slavery.

Mosby served as Grant’s Virginia campaign manager, and became a Republican, no small change for a former Confederate soldier in a political landscape of Southern Democrats.

Mosby said, “General Grant was as much misunderstood in the South as I had been in the North.” At a chance meeting in DC, President Grant thanked Mosby “for my getting the vote of Virginia.”

Mosby paid, however, for his political courage in Warrenton with threats against his life, the destruction of his childhood home, and at the sufferance of his legal practice.

Mosby wrote, “There was more vindictiveness shown to me by the Virginia people for my voting for Grant than the North showed to me for fighting four years against him.”

Mosby found it remarkable when Alexander Stephens was sick that President Grant visited him; Mosby said, “It looked as if our war was a long way in the past when the President of the United States could call to pay his respect to the Vice President of the Confederate States.”

Mosby said when “a dispatch announced [President Grant’s] death, I felt I had lost my best friend.”

Mosby was buried in Warrenton, Virginia and I visited his grave site a few days ago because his life was a lesson in reconciliation and re-union that we need to embrace in these days of national strife.