Bonnie’s Country Kitchen is a bustling gathering of friends and neighbors on a Saturday morning, catching up on the week’s gossip, family news, and chowing down on some fresh eggs and bacon, or pancakes, and as much coffee as it takes to get going.

This past Saturday, Bonnie’s was hopping, on this unseasonably warm and comfortable January Day, the tables full, persons leaning into the food on their plates and so they could hear their table mates, sitting back every once in awhile to say hello to a friend or neighbor coming through the front door, heads craning to catch a glimpse who that was.

There was a lot of animal hunting camouflage, an array of woods’ designer clothes, some winter beards to ward off the frigid air, ordinarily the rule this time of the year, and some hungry and tired families from warming themselves against the colder air hours earlier when they were out in the fields hunting. There was not a lot of talk about what they snared.

“I cleaned off the camouflage I put on my face earlier,” Charles “Charlie” Smith said, matter of factly, “as he took another gulp of Bonnie’s finest java.

“See ya Billy,” half rising to great a friend, Charlie explained, “I was supposed to go turkey hunting with my grandson, Jackson Rippeon, he’s 17, but he was behind in his school assignments, so we’re going quail hunting together on Sunday instead.”

“Get any turkey?,” Charlie was asked. “Not today,” said Charlie.

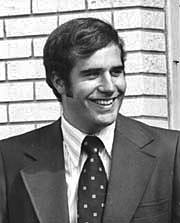

Charlie himself was born in Brunswick, went to Brunswick public schools, Frederick Community College, and the University of Baltimore, graduating with a BS in 1973.

“My Dad, his name was Joseph, was told by his stepfather that the men in ‘this family’ don’t graduate from High School,” Charlie said, “but my Dad wanted both his children to graduate college. My older Sister, Jo Anne, she was an A student. I was more athletic. I was good at baseball and soccer. But we both did graduate. That was one of the things he wanted for his children.”

“See ya buddy,” Charlie said to another passerby, like a seasoned politician, which he is, or Charlie might say, he was.

“In politics, you have two masters,” Charlie said, “there’s the elected position, and perhaps you shouldn’t be paid much to serve, and there’s your job or business, and the balance is not an easy one to hold.”

Charlie thought of law school because of his interest and early success in politics but he liked and did well mastering the challenges of air conditioning and heating but, before any of that, when quite young, Charlie was drawn to politics.

“It was in the third grade, 1956, my first campaign,” said Charlie, “I worked for Adlai Stevenson. I loved history since I was a ‘little fella.’”

“At our family dinner every night,” Charlie said, “we talked politics and history. I can’t understand how so many people today know so little about either politics or history, not even the names of fairly recent historical figures. I had someone ask, ‘What country is Texas?’ I carried this tradition forward in my own family of dinner table conversation about current events and what went before.”

Father Joe Smith worked at a gas station, Spurl, and then went into the Army, served in the front lines in World War II, from the beginning of the war to the very end.

“Dad saw a lot of action,” said Charlie, “a bomb hit his tank and he crawled out but he had a severe concussion, and that led to Pick’s disease, a shrinking of the frontal and temporal lobes that causes one form or other of dementia years later. Dad helped to recapture Paris and was in the Battle of the Bulge.”

This was the last major German offensive on the Western Front, in the heavily forested Ardennes region in eastern Belgium, Northeast France and Luxembourg. The Allied Forces were caught off guard and Americans suffered the highest casualties.

“Dad made it to a creek,” said Charlie, “and that’s how he escaped to survive the War.”

It was hard to escape history at the dinner table when you had a Dad who had been through such a war.

“If my Dad were here,” said Charlie, “and we went hunting, he wouldn’t fire a gun. He never fired a gun after World War II. He told me, ‘I killed enough in my lifetime, don’t need to kill any more.’”

“My Daddy worked on the Railroad,” said Charlie, “and so I had a hundred sets of parents. All our Daddies worked on the Railroad.”

“I made the plunge into local politics in 1970,” said Charlie, “when a mentor, Prof. Roger Shaw, from the Frederick Community College, recommended that this ‘young kid,’ myself, help his colleague in a local election, and his colleague won big in Brunswick and Petersville, and the local Congressman, Goodloe Byron, heard about what I’d done, and asked if I’d like to be an aide in Washington. I was then 21.”

Charlie had a gift for the political game, he was a whiz at it, a “whiz kid.”

Congressman Byron represented the 6th CD from 1971 until 1978; he had earlier served in the Maryland House of Delegates and State Senate. Both his parents had represented the 6th before. His wife, Beverly, won his seat after his heart attack in 1978. And so Charlie got to work with the crown prince of a local political dynasty.

“I worked on the Maryland Campaign for George McGovern,” said Charlie, “that shouldn’t surprise you, I was a Southern Democrat, never voted for a Republican.”

Then a seat opened in the Brunswick area in the State Legislature. Was Charlie ready to run? Was this his time to go from political operative to the candidate himself.

Charlie said, “I filed for the seat. I was 25. A well-known farmer filed the last possible day in the primary for the same seat. But I won the race by 116 votes. I ran in the General Election as a Democrat against the President of the School Board running as a Republican. The teachers hated him and the UTU supported my bid because, well, Brunswick is ‘Railroad,’ UTU’s constituency. I had 8 years in the State Legislature. I got to put my feet under the Governor’s desk, talked with the ‘Boss,’ that’s the Governor, handled complex banking matters, helped establish a full time People’s Counsel in utility cases, traded strategies, language, and inside information at political watering holes. But then came the time to work out the balance between service and a profession or job. So I became a full time business man.”

Charlie plainly loved the “business” and he left the Democratic Party for the Republican party.

Laurie Hailey joined Charlie at the table, and agreed, “He loves the business of politics.”

“It took me a long time being raised in a Southern family,” said Charlie, “to become a Republican. There was no party in the middle I could join. I’d prefer to join the ‘Common Sense Party’ but we don’t have one of those yet.”