“Black Panther,” the movie, has been rightly heralded as a cultural shift and a praiseworthy change for featuring a black hero as the lead, celebrated by a widely diverse and enthusiastic audience, with many moviegoers going back to watch this flick again.

A noble and courageous African nation with special gifts in spirit, science, and a unique mineral resource, kept secret from the world for fear of the world beyond its shores, headed up by an enlightened warrior king, “the Black Panther,” realizes it must share its treasures in the hope of a closer world community.

The movie serves, in the telling of this mythical action story, as somewhat of an antidote to the pathogens of intolerance infecting our nation.

The KKK is presently emerging from history’s slimy dark shadows to recruit newly discovered bed-sheeted members to its hate-filled agenda of bigotry, lies and violence.

National “leaders” insist, in irresponsible reveries of indifference, that there’s nothing wrong with white supremacists waving lit torches, brandishing hand guns, crushing innocents who protest peacefully, or ranting unceasingly their hate-filled propaganda.

“Black Panther,” the movie, may fairly be said to invoke the Reverend Martin Luther King’s oft-repeated message that we are headed toward a better day in the long curving arc of history.

The counterpoint to this hero is an earlier one, representing more where we’re stuck presently than whence we strive to arrive.

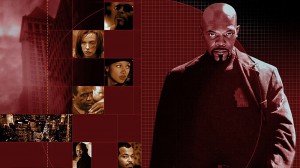

John Shaft, a fictional black NY police detective, from the 15th Precinct, in a dark long-leather coat, that swayed as he strut the streets, dwelled in the unfair gritty reality of the street, and of crime and corruption.

Shaft never lost sight, however, of what was just and right, despite the too often lawless cityscape that engulfed his life.

“Shaft” features Samuel Jackson as the rogue Detective investigating a race-based killing by the rich white son of a NY developer, played by Christian Bale, who says in his defense, “He started it. I finished it.” No question Bale is the embodiment of the white racist at the threshold of a dystopic “system” of justice that favors Bale.

When Jackson walks the street, we hear Shaft’s top-of-the-charts Emmy-winning funk-styled theme song, written by Isaac Hayes, about how Shaft’s “a complicated man but no one understands him ….” The heroic in Shaft is his moral worth, how he resolves to fight for the right in such moral chaos.

The black victim arrives at a fashionable downtown Manhattan restaurant with a white woman.

Bale shouts out, “You know they don’t serve malt liquor here,” pauses, and calls him, “Tupak.”

The intended victim is dressed well, but Bale doesn’t think he belongs. Like life, much is implied and unsaid, while still known and understood too well.

The derided object of Bale’s racist remarks takes a white napkin from the table, cuts out the eyes and mouth, so that it resembles a KKK cowl, and drapes it on Bale’s face, to general laughter by patrons and Bale’s friends.

In response, Bale follows his victim outside, and, unprovoked, takes a bronze pipe, and, from behind, crushes his victim’s head.

Black lives don’t matter that much to Bale.

A waitress on her break sees the attack from the shadows, is scared half to death, and paid by Bale’s developer dad to get lost.

The system “works” better for some than others.

Bale skips bail and returns two years later, greeted by Shaft at the airport, who says, “How ya doin’ Richie rich?”

When the court releases Bale again, despite the fact that he fled the jurisdiction for two years, Shaft hurls his gold shield from behind the jury rail, seemingly right at the judge, but it sticks solid on its sharp edge in the august mahogany wall just behind the judge.

There is the fury that comes in the face of what’s unfair when the white and rich are treated “differently” than persons of color.

Shaft quits the force on the courthouse steps but continues to work the case – as that’s who Shaft is. Shaft finds the waitress after much violence, chase scenes, strange alliances, near death confrontations and she agrees to testify.

While Shaft is off the force, he uncovers two corrupt officers prepared to kill the waitress witness.

When Bale arrives at court for the trial, the victim’s mother shoots Bale dead, convinced she can’t trust the “system” to get it right.

There is a price to pay when the public loses its trust in the law.

Shaft is fiction but the intolerance so easily suffered by so many, and the stark injustices in our just us system, betray our nation’s original promise of equality and fairness, and I’m not just talking about the “moving pictures.”