Russell Baker never thought he was eternal, and may not have appreciated how much pleasure he gave us all as a reporter, humorist and columnist, but surely he’d rather we thought of him – as just “gone for now.”

In truth, Russell Baker left us on January 22, 2019, at 93 years of age, after a fall, after a lifetime of having written barrels of ink on almost anything you can imagine, talking more hours than many people live, and hosting Masterpiece theater.

Russell was the local boy who made good as he was from nearby Morrisonville.

Russell won the Pulitzer Prize for his writing, commentary and his own biography, “Growing Up,” about how three strong women helped him “amount to something.”

I got to sit and talk to Russell about his whimsy and irreverence a few years ago.

In his “Poor Russell’s Almanac,” he insisted the “English language had a word shortage.” There were things we daily observe but have no word for; also, there are words we use all the time that don’t mean what they appear to say, for example, “peace with honor,” really means, “war.”

Russell wrote the story of (a fictional) Robert who complained to his wife that he “wasn’t being relevant more than ten minutes a day” and asked if a “relevance transplant would help.” Robert’s wife noted how “[m]any persons with only four hours of daily relevance capacity hold very respectable positions nowadays.” But Robert wouldn’t have anything to do with “relevance.”

A co-worker of another imagined character says, “I was telling my roommate what a beautiful sense of guilt you have.”

Charles Kaiser, an author, former New York Times reporter, Wall St. Journal columnist, Newsweek media critic, and close friend, described Russell as “a national treasure.”

After serving as a police reporter for the Baltimore Sun, Russell joined the Washington Bureau of the New York Times to cover Washington, the White House and presidential politics.

His by-line appeared over more than 4,000 “Observer” columns (three a week for the New York Times) with his signature brand of humor (one collection of columns is titled, “No Cause for Panic.”)

Russell wrote marvelous “treatments” of noteworthy books (for the New York Review of Books) (refusing to say they were “reviews” — as he thought it unseemly to dispose critically of an author’s long hard work at writing in a 4,000-word review) ( “Looking Back – Heroes, Rascals, and Other Icons of the American Imagination,” contains several of his outstanding “reviews”).

Not to be outdone by Benjamin Franklin, he wrote his own “almanac” with many marvelous observations, several mentioned above, and, of course, quite a number about the Capitol and politics, for instance: “The dirty work at political conventions is almost always done in the grim hours between midnight and dawn. Hangmen and politicians work best when the human spirit is at its lowest ebb.”

A close friend, Art Buchwald, wrote a tongue-in-cheek blurb for one of Russell’s books: “I refuse to say a nice thing about Russ Baker. I have no intention of helping him get ahead in this world.”

Baker once described Murray Kempton as a “writer” and “not a plain reporter,” and a “man learned in history, acrobatic in grammar, skilled in irony and willing to use it” and able to “laugh at the pretensions of his own trade.”

Baker could have been writing about himself although Charles Kaiser said, “the difference is you always knew what Baker meant.”

Russell got to comment on British mores as the host of Masterpiece Theater (succeeding Alistair Cook); he confesses, however, that he thought some friend was playing a joke when he was first invited to take on the assignment.

The golden thread weaving through what Russell has said and done is an elegant and honest telling of the stories that make a life. We all like a good story.

In his memoir, “Growing Up,” Russell describes how his mother was after him to decide what he’d become.

When he was 11, he showed her a composition he’d written and she said, “maybe you could be a writer?”

Russell recalled: “I clasped the idea to my heart. I had never met a writer, had shown no previous urge to write, and hadn’t a notion how to become a writer, but I loved stories and thought that making up stories must surely be almost as much fun as reading them. Best of all, though, and what really gladdened my heart, was the ease of the writer’s life. Writers did not have to trudge through the town peddling from canvas bags, defending themselves against angry dogs, being rejected by surly strangers. Writers did not have to ring doorbells. So far as I could make out, what writers did couldn’t even be classified as work.”

Russell who lived in nearby Morrisonville when young, said, when he left Morrisonville for Lovettsville, “it was like going to Washington, DC.”

When a cloud of dust was spotted, you could hear the screen doors slamming, he said, everyone gawking, to see the passing car. He said there was no electricity. No running water. You went to sleep when it was dark. You arose when it was light.

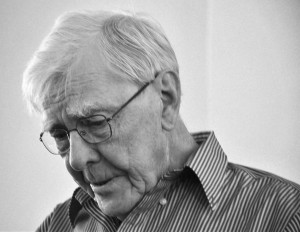

When I last saw Russell, he spoke in a soft voice, his hair falling light on his forehead, recounting what it was like when he lived a few miles south of Lovettsville when his mother insisted he had to make something of himself.

His mother always knew he would make something of himself. And so have many found who have loved the words he wrote and spoke.

He is gone for now but his work remains to inform, inspire and entertain.