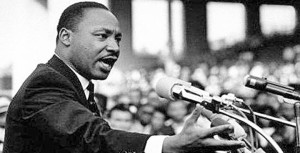

MLK: “Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force.”

There’s a big difference between condemning religious fanatics slaughtering a dozen unarmed political French cartoonists for satirizing the prophet Mohammed, and endorsing the content of their satirical expression that is plainly offensive to the non-violent Muslim faithful.

It’s a corollary of free speech that coercion against anyone based on what they express by cartoons, prose, or the spoken word is a fundamental violation of “free” speech.

On the other hand, there is hardly anything more destructive of comity in a world so ready to war, than the express or implicit endorsement of satirical disrespect for the founder and prophet of any religion.

Some say: “What does it matter what they publish?”

Since when have we endorsed freedom without responsibility?

How many are comfortable with disrespectful satirical attacks against their own religions and distasteful remarks that may include Krishna, Zoroaster, Abraham, Moses, Lao-Tsu, Buddha, Confucius, Jesus, Martin Luther, John Calvin, George Fox, John Huss, John Wesley, Swedenborg, the Bab, Baha’u’llah, Brigham Young, Mary Baker Eddy, Joseph Smith, or Gandhi?

One million magazines containing these disrespectful images were sold following this grisly slaughter.

We convened a million person march in Paris to protest killings calculated to still freedom of speech but we’re apparently unable to parse the separate question, whether we approve of disrespect against those religious having nothing to do with the killings.

Nor is this just about timing.

There should be some cultural and personal standards of conduct that are sensitive to a non-believer’s disrespect.

Is this offense, making light of a religious leader, and a prophet, anything like the throwback who just has to use the offensive racist N-word?

I think so. Continue reading →